| |

The Tolerance Project: A MFA

The Tolerance Project Archive homepage

The Tolerance Project Donors

Sandra Alland

Gary Barwin

Emily Beall

Joel Bettridge

Greg Betts

Christian Bök

Jules Boykoff

Di Brandt

Laynie Browne & Jacob Davidson

Kathy Caldwell

Angela Carr

Abigail Child

George Elliott Clarke

Stephen Collis

Jen Currin

Moyra Davey

Anonymous Donor

Thom Donovan

Sarah Dowling

Marcella Durand

Kate Eichhorn

Laura Elrick

Jennifer Firestone

Rob Fitterman

Jenna Freedman

Dina Georgis

Barbara Godard

Nada Gordon

Kate Greenstreet

Rob Halpern & Nonsite Collective

Lyn Hejinian

Susan Holbrook

Catherine Hunter

Jeff T. Johnson

Reena Katz

Bill Kennedy

Kevin Killian

Rachel Levitsky

Dana Teen Lomax

Dorothy Trujillo Lusk

Jill Magi

Nicole Markotic

Dawn Lundy Martin

Steve McCaffery

Erica Meiners

Heather Milne

K. Silem Mohammad

Anna Moschovakis

Erín Moure

Akilah Oliver

Jena Osman

Bob Perelman

Tim Peterson

Vanessa Place

Kristin Prevallet

Arlo Quint

Rob Read

Evelyn Reilly

Lisa Robertson

Kit Robinson

Kim Rosenfield

Paul Russell

Trish Salah

Jenny Sampirisi

Heidi Schaefer

Susan Schultz

Jordan Scott

Evie Shockley

Jason Simon

Cheryl Sourkes

Juliana Spahr

Christine Stewart

John Stout

Catriona Strang

Chris Stroffolino

Michelle Taransky

Anne Tardos

Sharon Thesen

Lola Lemire Tostevin

Aaron Tucker

Nicolas Veroli

Fred Wah

Betsy Warland

Darren Wershler

Rita Wong

Rachel Zolf

Office of Institutional Research

Communications & External Affairs |

|

Susan Schultz

Tinfish Editor's Blog

My dear times' waste": Shakespeare sonnet XXX, Tortillas, & Dementia

This past Wednesday, we inaugurated English 410 (Form & Theory of Poetry) with a discussion of one of my favorite Shakespeare sonnets, #XXX, which begins, "When to the sessions of sweet silent thought / I summon up remembrance of things past . . ." The sonnet works as a fugue of metaphors--legal, financial, emotional--that circulate against the central metaphor of the poet's mind as a courtroom where memories are brought forth and weighed as evidence of his losses. The judge's gavel comes down with the happy ending in the final couplet, where the poet's thoughts of "you" make all things right, losses turned to gain.

One of the things I love about this sonnet is the way that the word "sessions" opens up the entire poem, once you linger on its legal connotations. The economy of the poem is so tight (so in the black) that words like "grieve" wobble productively, pointing to the complaints our memories bring back in our mental courtrooms, and to the grieving we do afresh each time we remember. That we grieve for what we do not remember only adds to the affect (and effect).

I told the story of my daughter's encounter with the difference in meaning between words of the same sound. When she was first learning English at age three--her first language was Nepali--she wanted to know what my husband was making for dinner one night. He responded that he was making tortillas. Now, our cat's name is Tortilla, so what ensued was a very long evening during which she repeatedly demanded to know if we were going to eat our cat. (What made the long story even longer was that my husband eventually said yes, out of frustration with her unwillingness to take no for an answer.)

Tortilla, tortillas. Both are nouns, but one we do not eat. A lesson learned through tears. It was a story my mother would have loved, or loved to tell, had it been hers. She was a wonderful story-teller, and many of her stories were about words. I remember one about a young soldier who greeted her each day in Italy during the Second World War by yelling, "wanna marry me, Marty?" My mother got tired of the greeting, so she asked the military chaplain to walk with her one day. When the soldier called out his greeting, she said, "Yes! Right here and now!" That put an end to his greeting, that promise to enact his words as a deed (of marriage). There was the less happy story of a pilot she knew who told his girlfriend that if she did not marry him, he would not return from his next mission. She said no and he did not. Whether there was volition in his disappearance or just another random act of war no one would ever know, just as we often fail to know the ends of our words' stories.

These stories came to mind when I telephoned my mother yesterday. For two or three years now her responses on the phone from her Alzheimer's home have reminded me of the language tapes I used in college to learn German. The tapes employed repetition and small variations (moves from past to present, present to future in shifts of vowel) as ways to impress verb forms and phrases in the mind. So my mother would say each week, "I'm so glad you called and that everything is all right. It's important to know that everything's all right." Then she would want the conversation to end (she never lost the sense that long distance phone calls cost a lot of money and should be kept short). She would sometimes vary things by answering questions about the weather, or the food she was eating. Sometimes she said she was happy there.

This time, there was silence, not rote repetition. I spoke into the silence, but I'm not good at inventing talk in thin air. I asked if she was there. She said, "yes, I understand," and then went quiet again. Never before has there been such pause between words, even words that didn't mean much except that we were still speaking them to each other. She is losing speech, even as she loses weight (seven pounds this month). Where stories ceded to phrases, the phrases now succumb to quiet.

I needn't have gotten up at 4 a.m. to see Teddy Kennedy's funeral; there was much gathering of people and vehicles and media chatter, and the ceremony did not begin for over an hour. Yet I'm glad I did. Leaning on his son's arm, Sargent Shriver was ushered into the cathedral, muttering as he went. The reporters told us that he suffers from Alzheimer's, had just recently attended the funeral of his wife, Eunice, and run after the hearse perhaps a bit inappropriately. That the family chose to have him in church says much. That they did not hide him from the public strikes me as a model for the rest of us. My mother's home, albeit lovely in spirit and space, can be entered only through a door that requires a combination to get in. It's a sealed place; the gardens form a circle that cannot be broken. The Kennedy's broke that circle, making us all witnesses to the Alzheimer's sufferer not as someone else, but as one of us.

[Martha J. Schultz, February, 2009]

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 12:04 PM 1 comments

Labels: Alzheimers, Dementia and poetry, teaching poetry

Thursday, August 27, 2009

Economy and the Haiku: Basho and the Recession of 2009

At the ancient pond

a frog plunges into

the sound of water (Basho)

The last time I taught American literature since 1950 an odd thing happened. The contents of the course and the contents of my life folded together like an accordian. I would teach a book, then seem to enter it, move on to another, and enter that one. The first such incident attended our reading of Catch-22, by Joseph Heller. That farcical-tragic novel features a wounded soldier called "the man in white." No one knows quite if he's alive or dead; he simply lies on his hospital bed, his leg propped up in the air, and other characters stare at him, try to suss out whether or not he breathes. So I was driving home on the H1 freeway one day, about to merge into the right lane after the Pali turn-off, when I looked to my right and gasped. Beside me was an odd ambulance with uncurtained back windows through which I saw a person wrapped in a white sheet, his arms raised in the air. The man in white.

Later synchronicities included hearing from a former civil rights worker (he'd been an aide to Stokely Carmichael) as we read Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon; this man was moving to Maui and wanted to talk about how to publish his memoir. Then, as we read Maxine Hong Kingston's China Men, I found myself in a meeting with an immigration lawyer and a graduate student from China I was sponsoring. She was trying to stay in the country. The lawyer asked her how her name is transcribed in English, as a word, or by syllables. This (and much else) happens to Chinese immigrants in the book. Memory won't offer up another example just now, though I'm certain there was one.

And so today, a couple of years later, I sit down to read haiku by Basho for my English 273 (Creative Writing & Literature) class. On my syllabus the students will read, "Monday, August 31: Hamill. (Buson) Go to the Krauss Hall pond . . . this week and sit for a while." Many of us who work at UHM walk through the pond area on our way to our offices; it's one of the few spots on campus that suggests community. It's alive with cats, carp, turtles, and waves of old and new ducks. One tree blooms purple, sheds its blossoms into the water, blooms again. Any change to the pond causes consternation in the faces of the resident custodian and those lucky souls who work in the building that surrounds the pond on three sides. One of my mother-in-law's cats was found by the pond.

As I begin my reading, I get an email from my colleague, Jon: "Bien the groundskeeper told me today that this weekend all the ducks will be removed from Krauss Hall, permanently, along with most of the fish."

The Ron Padgett Handbook of Poetic Forms, which I have assigned to my students, defines haiku as "a 'poem recording the essence of a moment keenly perceived in which nature is linked to human nature.'" To which one might add that it is a poem about deeply felt transiences. One of my favorites is about the longing Basho feels for the very place in which he is:

Even in Kyoto,

how I long for Kyoto

when the cuckoo sings (Hamill, 39)

The sense of repetition ("I long for Kyoto, while in Kyoto") is intensified by the cuckoo, which tends to sing twice or more (at least when my husband's clock is working well!)

Padgett's definition is quite secular; nowhere does he mention the moon-viewing huts one sees in Japan near Shinto shrines. Nor does he mention Buddhism, its emphasis on transience. But what I miss at the moment is the clear link, not between "nature and human nature," but between "nature and human economy." For it's the state budget cuts that are lopping away at these few places where nature inhabits the university, provides a spot to watch the animals and each other. Whatever the cause, however, I will miss Krauss Hall pond as I sit at Krauss Hall pond and remember the ducks that are no longer there.

Even by Krauss Hall pond

how I long for Krauss Hall pond

where ducks swam and quacked.

On another note, one that wrought-irons together (hat-tip to Amalia Bueno of English 410 for that verb) the poor economy and book publishing, I've been asked to spread word of the University of Alabama's Modern & Contemporary Poetics Series "recession special." Among others, my book of essays is on offer at half its list price. Such a deal may never happen again, if we're lucky. Although I did buy Tyrone Williams's first book of poems the other day on amazon.com for one cent. Postage extra.

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 3:13 PM 0 comments

Labels: Basho, teaching poetry

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

Chant 15 (way after Whitman)

--The passenger sits in 44G, beside the toilet. The flight attendant's husband is driving eight hours home to Albuquerque, because he likes to sleep in his own bed. He's too old for that.

--The distant relative whose son died young in California is not allowed to see her grandchildren; something about a will.

--The relative she'd never met says her father was "the accomplished one." Says his state hasn't had a governor for a year and a half because she wants a job with Obama. She counters that her governor worked for Sarah Palin. The dentist was an English major at Michigan. His wife's cousin died young in Honolulu.

--She will not, cannot, sleep between the bride and the groom, but they married. The minister, his degree purchased on-line, spoke about the Odyssey, Ulysses and Penelope, marriage as community. "That went right over my mother's head," one said.

--"It's not my mother-in-law, it's my wife's mother-in-law who is the problem." She still makes the strong one weep, the ex-drinker drink, the ex-smoker smoke. She says the forks and knives are wrong on the table, the grandson is not respectful, and the new President is "a Negro."

--The poet watched the Tour de France on his suburban television, rode his bike after.

--The young soldier in desert fatigues waits for his backpack to come round the airport carousel. He holds a small camouflaged pillow in his left hand, a cell phone in his right.

--Pigeons fly in and out of the top windows of the Detroit Free Press building. Inside an empty room the blown-up headline, "Men Land on the Moon" covers part of one wall.

--He and she broke up with him and him. He was a "user"; he was "manipulative." No TROs, but.

--The building with trees growing from the top, crude paintings in the windows, is due to be imploded.

--When she was there, they would not give her the courses she wanted to teach. When she was leaving, they offered them.

--The Greek man scoops chili and dogs in the window of Coney Island Hotdogs. Just down the street a man sits on the sidewalk, reading his Bible. Tourists arrive, speaking Italian; our Benedetto talks to them from the next table.

--The retired pressman constructs the Bounty in his garage, the scale larger than usual to aid his arthritic hands. He does not want detainees in a Michigan high security prison. The ship is for display; it will not float.

--The suburban houses are all, it seems, for sale. Three are abandoned up the street. The young man at Coney's handles foreclosed properties in the city. One on his list for $750. It's just a shell, he says; you have to fix it.

--The bride's mother weeps at rehearsal. "Stand at a 45 degree angle for the photos; I'll just take a few."

--The poets eat on their deck, talk about memory, the way it changes, public/private Facebook communication, the PDFs that will draft memoirs, the dangers of public private memories. Of lyrical essays about Detroit, all lament and no fact.

--Ichiro, in right field, constantly stretches. His practice throws stylized, his batting stance pigeon-kneed. He throws the Tigers' winning hit into the crowd.

--"My mother-in-law is terrible. She said awful things when Michael Jackson died."

--The young women talk in the restroom during the wedding reception. "He's got what he wants from you."

--On Belle Isle the diners are all white, the servers black. "I saw the mayor earlier." He played in the NBA. The island is all Canadian geese and pigeons, tall grasses. A middle-eastern couple walks toward the shore; a few black men fish; a woman barbecues for her daughter after the rain.

--The poet does not like the wisdom position. His interlocutor distrusts bitterness. "I understand that a lot better," he says. "You can't just fix it now."

--The middle-aged flight attendant is dating a man she probably doesn't want to marry. He lost his job; she feels sorry for him.

--His cousin lives in an artist house downtown. Farming is art in abandoned lots. He took video for Toyota; she takes photos for magazines in Birmingham. Her "own" photos are of naked women; they need to accept themselves as they are, she says. We wait for scallops, crepes. The man who makes my crepe drops the pan twice on the carpet.

--He's the only Asian at the wedding. When he friends me later, I see his name is Polish.

--The Ethiopian driver drives a burgundy van, puts on his dress hat. A cross hangs from the mirror, says Jesus loves us. The passenger asks what brought him to Detroit. He moved to Erie with his wife and six children (one his sister's); moved on to Detroit to get work. His wife stayed, a divorce. This bothers him, because he tried. Someone put him in touch with a woman back home. He is traveling to see his mother, marry this woman. A big trip. Please pray for him.

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 10:55 AM 0 comments

Labels: Detroit, Ichiro, Whitman

Monday, August 17, 2009

Travels in place: Detroit (and O`ahu)

A dream: somewhere near a large city (I'm thinking Seattle), walking out of the small town where I was staying, thinking I could return in a large loop. Walking until near dusk. Stopped in a hotel and walked up some stairs. Suddenly emerged on a platform from which I saw high mountains (looking more like the sheer, corduroyed Ko`olaus than anything in Washington State). Beside me was a large dam. Water flowing everywhere--waterfalls on the mountains, closer by, then on the dam. I went downstairs to ask a hotel employee where my small town was and if I could get there by nightfall, but I'd forgotten the town's name.

The father of an old friend, a man who'd grown up in Germany and emigrated to the US after WWII, once told me that he no longer remembered which cities he'd traveled to and which he'd imagined.

Tomorrow night I travel to Detroit for a young cousin's wedding. Without having seen it, it would be hard to imagine Detroit, the less glamorous L.A. of the midwest, dying at the center and the peripheries, where foreclosure rates skyrocket. Two summers ago we traveled to see my cousin, who lives in Shelby Township, and my 91-year old aunt, who lives in Troy (like my dad, she grew up in Romeo, once and still a farming area, though the suburbs and strip malls approach from the south like a large generic storm). My cousins grew up in Highland Park, near (I think) the old Chrysler factory (here's something on Highland Park's Ford factory), an area that for decades lacked police or fire department, full of large houses, some of which are still intact (if weary-looking) and others that are burned out. I don't know if this was the Chrysler plant where my father worked, fresh off the farm, for a year he remembered as an object lesson in moving on (which the military helped him do when it drafted him in World War II). The old car plant is empty and, like much of Detroit, there are a lot of vacant lots, abandoned and boarded up houses, broken stuff. There had been Dutch elms until the blight wiped them out in the 1970s. Nearby was the site of Vincent Chen's 1986 murder at the hands of unemployed, aggrieved and racist auto plant workers. Mark Nowak's poem is worth a visit, some time spent. The poem alternates with photographs of the abandoned factory; one bit of graffiti goes, "FACTORY BUILT MALICE." When Chin was attacked, he was taken to Henry Ford Hospital, where he died. One of Detroit's tragic histories can be located in that sentence alone.

[Highland Park, 1956]

[Highland Park, circa 2007]

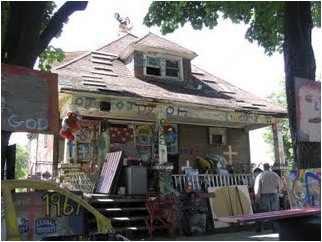

One of the most interesting places in contemporary Detroit is the Heidelberg Project area, where Tyree Guyton began making houses, vacant lots, and even trees over in the 1980s as art spaces. Twice the project was partially demolished by the city and twice it reemerged intact, if you can call it that, the beauty of recycled decay. Here are some photos:

Note the cars with crosses on them, which remind me of this church sign in the suburbs of Detroit, the centrality of cars to the secular and religious economy of the area is clear:

This sign piggybacks nearly seamlessly onto this call to prayer for the Detroit Tigers baseball team:

The graffitied houses also force us to reread history: 1967 (the year of the Detroit riots, after which most whites fled the city); OJ; Oklahoma City. The word scatter matches the conceptual scatter a spectator feels when she sees these houses. To say nothing of the panic she felt when Tyree himself appeared and demanded to know "the purpose of art!" In a city that was born and thrived for a time on use value, the relative uselessness of these houses--no one lives in them, after all--seems especially striking. Down the street a ways, my cousin Bill, his daughter, and I ran into some art grad students from Wayne State. They wondered where to find old tires for a new project; some were setting out in clunkers to hunt down their treasure. We felt confident they would find plenty. Recycling for art's sake, where art cannot be for its own. Reminds me of the alternative economy of Tinfish journal covers, the last of which was made of real estate magazines, the kind you can pick up for free around town. They point at the artifice of our (of any?) housing market, as the wacky beauty of the Heidelberg project highlights Detroit's destruction by forces beyond its control.

One of Bill's relatives offered me an embodied definition of "Reagan Democrat" when he blamed Coleman Young for the death of the city, for getting whites to flee by making it clear they weren't welcomed. What a lot of history gets rewritten in our assumptions of what it means.

We mostly stayed home this summer, which provided time to get to know this place a bit better. I became a big fan of 1970s era government studies--a study of the Kawainui Marsh in Kailua and one of what became, in part, the Ho`omaluhia botanical garden near Kane`ohe. The old photos are amazing documents. One in particular is of the He`eia bridge near the state park (which was a place where souls were judged and separated); in the 1920s photo, there is no vegetation around the bridge at all. When I ride my bike over it now, by way of contrast, I can hardly see a thing because the mangroves are so thick. It seems a reverse haunting to see what was not there as present in one's imagination of history. These reverse hauntings are everywhere in Hawai`i. That's something I learned from my brief time in Detroit.

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 11:28 AM 4 comments

Labels: Detroit, Hawaii, Heidelberg Project, Mark Nowak, Vincent Chin

Saturday, August 15, 2009

"Good grammar is always glamour, girls":

Goro Takano's With One More Step Ahead

Years ago, around the turn of the last century, as one might say, I bought a copy of Richard Wright's haiku via the internet. It wasn't that I was a Wright fan, though Native Son had a big impact on me in high school. Nor was it for love of haiku, a form I appreciate mainly in the abstract (though I'll be teaching haiku in a few short weeks). I got the book of Wright's haiku because we were admitting a student to our Ph.D. program--a Japanese national--who had written on them. It was rumored that the student's mother was an important tanka writer in Japan (I have no idea if that is true). As someone whose primary memory of Wright involves an alarm clock, a rat, and a Chicago tenement, the haiku surprised me. They seemed so classical, so wrapped up in nature (despite their provenance in Paris), so faithful to the intentions of their form. "In the damp darkness, / Croaking frogs are belching out / The scent of magnolias," goes #227. Equally intriguing was the Japanese student of Wright, one Goro Takano, whose English was quick, word rich, and accented. Once we were on speaking terms in the hall, I asked him how the Richard Wright project was going. He indicated he'd moved on.

Goro returned to Japan to work on his dissertation. I got an email from him, asking if I'd direct it; it had become a novel, he said, and he'd been working on it for years. He'd started writing in Japanese, then turned to translating the manuscript into English. It had taken on a life of its own in English, insisted on being written in this "stepmother tongue." One of the novel's characters, in other words, was a language that was not its writer's blood relative (not sure I like this parsing of blood and not-blood, but there you have it). As a poet I was unsure how to take this request, but Goro sent writing samples, odd parables more reminiscent of Kafka than Ernest Hemingway or Raymond Carver. So I said yes. It proved one of those marvelous dissertations that directs its director. I was left to fling pages full of questions at Goro by email slingshot, not so much to recommend revisions as to help us both through knotty philosophical and literary issues. "Is this a Japanese or an American novel?" I remember asking at one point.

Now, on reading the proofs of the large novel--With One More Step Ahead--from Blazevox [books], I realize how little meaning that question ever had. This novel is post-national in the best sense. An American-language novel with African American influences, its primary subject is the amnesia suffered in post-World War II Japan. An American novel, it involves a lot of Hawaiian material. A novel in part about Hawai`i, it engages the Japanese fascination with these islands. The novel owes a lot, perhaps, to the contemporary Japanese writer, Haruki Murakami, who has also written about Hawai`i, but its intellectual edge is sharper, its encyclopedic investigations of contemporary literature, film, and gender politics more attuned to the academic eye and ear. Ah, but what to make of a narrator/translator who suffers dementia, a husband/writer who communicates only by moving his eyeballs, a sex cultist named Cosmo who has no gender, a TV producer who wants pathos at the expense of his subjects' happiness, or the boundaries of the A-bomb dome broken by lovers who copulate on ground zero? If much of the energy of the novel is intellectual, it manifests itself in surreal, time-criss-crossing plots and subplots that will make it a page turner, once it escapes the pdf form I'm reading it in. Or is it that I simply haven't yet imagined it and me with a Kindle?

Amusing, yes, that Goro Takano, the expert on three line haiku, emerges here as the author of a 379-page novel (including bibliography!), its pages slathered with words, complicated syntax, an English that is not quite that spoken by a native--sometimes better. This reader became so involved in the subtle differences between her own English and Takano's that actual English words began to become foreign. Take the word "distressful." I was convinced it was the neologism of a non-native speaker until I looked it up on merriamwebster.com and realized that it IS an English word. Goro's prose enacts the (English) language in the process of being reinvented and rediscovered. It's an exciting read on many levels, but this is one that I find crucial to the overall effect of the novel. Nowhere is this as apparent as in the poems Takano includes in the novel, poems by Lulu, the demented narrator/translator. Lulu writes in various modes, including the ballad. Chapter 23 begins with a quote from John Ashbery's "37 Haiku" in A Wave: "He is a monster like everyone else but what do you do if you're a monster." Then we get Lulu's proto-Bob Dylan ballad, which opens:

Hard rain is falling down.

All over this small town.

Misty cold midnight.

Only a few city lights are on.

The poem's tone is odd, to say the least, rather like one of Ashbery's funny/sad poems. "Finnish Rhapsody" comes to mind, though that poem's not so jangly as this one.

Her dearest daughter is gone.

Run over by a truck.

That was also a rainy night.

Her kid was walking after her.

As it takes its nine page course, this poem comes to record the intense ethical conflict of a TV reporter over whether he should have saved the girl or recorded her death on film.

I can't say for sure if that poem was written in that way because Takano is a second language writer in English; in some ways, the poem reminds me of Sarith Peou's simple yet searing poems in Corpse Watching, also composed in non-native English. But there are moments in the book where the second language English emerges, making the writing more effective. Take "Lulu's Fifth Poem: 'Tanka: I Am.'" Ron Padgett's The Handbook of Poetic Forms defines the tanka thusly:

"Tanka (from the Japanese for 'short poem') are mood pieces, usually about love, the shortness of life, the seasons, or sadness. Tanka use strong images and may employ the poetic devices, such as metaphor and personification, that haiku avoid." (187)

Takano's / Lulu's poem opens in unsurprising English (the formatting is going to hell, sorry):

I am a spider

whose dewy web is still

missing many

warps and woofs; yet,

I am master of myself.

I am a mist

who spreads gradually

far and wide,

while still searching for

a chance to confine myself.

But as the poem goes on, its English gets less predictably English. Take this section:

I am a rain;

I won't chase anymore

those who scattered

away--Because, look, here's

someone waiting for me.

Or:

I am a mud

drying up with

a good number of

footsteps of the people

masking their true faces.

Or the last line of the final section:

I am a forest

who flourishes deep inside

of a newborn's mind;

as time goes by, maybe, I'll

be doomed to soil and wane.

Some native English speakers could come up with a line that combines "be doomed to soil" with "be doomed to wane," (the aforementioned Ashbery comes to mind) but something tells me the line is more easily arrived at if these words remain somewhat foreign. And phrases like "I am a mud" and "I am a rain," which seem to ask for the reader to take out the indefinite article, or to add something to the end, like "spot" or "drop," are effective precisely because they resist native fluency. They are more like lines from Peou's "Corpse Watching":

Corpse watching provides excitement,

Corpse watching is filled with fear

The corpses are someone's father, brother, sister, mother--

Sometimes corpse watching brings tears. (np)

It would be "better" English to write that "corpse watching makes me cry," but it would not be more effective communication. Nor would the first two lines benefit, in this context, from being "corrected" out of its cliches, its generalizations. Because, for once, these abstractions work--largely because of the Cambodian genocide that lurks in every line of this poem and the eponymous chapbook. But also because what Evelyn Ch'ien calls "weird English." She writes "about the ushering in of a global subjectivity, in which the diaspora consciousness caused a number of writers to relate their experience polylingually."

To read Takano's entire novel is to be constantly jolted by the often miniscule differences between one's own English and Goro Takano's English. We (native speakers of English) are constantly reminded that we, like Lulu, are translators of this text, even if our translations are from English to English. The frequent parenthetical interruptions by "Translator" emphasize this difference between the American novel we think we're reading and the Japanese content--and/or vice versa. While Ch`ien's interest is primarily in weird Englishes spoken by immigrants, or Pidgin spoken by non-dominant groups (see Lisa Kanae and Lee Tonouchi's works), Takano is a writer who studied in the United States and returned to Japan, where he is now associate professor of English at a medical school. So, while he is now teaching "weird English," he is not immersed in it. His English now belongs more to Japan than to the United States, although his book will find most of its readers in this country. How appropriate that his book be published by Blazevox, "a publisher of weird little books." At first I disliked that phrase, thought to tell the publisher, Geoffrey Gatza, as much. Now I get it. Weird is good, though this book is not "little" in any sense of the word. It's complicatedly astonishing.

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 3:49 PM 1 comments

Labels: "weird English", Blazevox, Goro Takano, John Ashbery, Lee Tonouchi, Lisa Kanae, Richard Wright, Sarith Peou

Friday, August 14, 2009

"Damaging impact Hinshaw": Cutting up a UHM budget cut memo

This past Wednesday we employees of the University of Hawai`i-Manoa received another in an increasingly long line of memos from our Chancellor, Virginia Hinshaw, about the sorry state of our budget. You can see the entire memo here. Suffice it to say, as the Chancellor does in her first paragraph, after the chirpy "Aloha!" with which she opens, that "we . . . the citizens of the State of Hawai`i, along with people around the world, are dealing with financial challenges that are also heavily impacting our university." The mind reels at that image of vague challenges impacting an abstract institution, but she quickly cuts to the chase, offering up numbers: $14 million of cuts, on top of 4% on top of $20 million. The photo at the top shows what nearly 20 years of cuts have already accomplished; this is my building, Kuykendall Hall, whose paint falls off as I type, whose elevator has never worked right, and whose offices are emptying out from retirements, moves, and soon-to-be layoffs.

Having set forth the problem, Chancellor Hinshaw immediately assigns blame. Is it our Republican governor, Linda Lingle, who refuses to raise taxes? Is it greed on the part of politicians, administrators, even the lamentable football coach (whose $1 million annual salary was cut 7% for an anti-gay slur)? No, it's the UH public employee unions, of course, who have not yet reached an agreement with the powers that be. And so, there will be "retrenchment," perhaps the only euphemism in the language uglier than the word it replaces, "lay-offs."

Lest we think the administration is not working with due diligence, Hinshaw lets us know that "over the past several months, members of our Chancellor's Advisory Committee on Prioritization and Budget Workgroup have been meeting separately and in recent weeks, together, to discuss ways in which UH Manoa can maintain our focus on academic priorities and, at the same time, maximize our limited resources more effectively, including the identification of areas of reduction/elimination and recommendations on additional ways to generate more revenues." Doesn't that make you feel better, oh employees of UHM?

Hinshaw adds some bullet points about our future cuts and exemptions from cuts. She closes by promising a "campus-wide forum" (does that sound to anyone else like a "town-hall meeting"?) where we can share our ideas. "This is a time for creativity and action; thankfully UH Manoa is blessed in having a lot of mind power to apply to our challenges. . . I am grateful for everyone's passionate support during these tough times." She signs off with the Hawaiian words, "Mahalo nui loa," and then leaves us to gather up her syllables and march forward into the future our creativity and passion(!) will have endowed us with.

I cannot do justice to the awfulness of our Chancellor's prose, but I wanted to do something to it. So I went to a cut-up generator, one of those computer programs that makes William S. Burroughs's work so easy--too easy, because actually chopping away at the words might prove a better release. But here's what happens when I take the the memo and cut it up multiple times:

“fiscal exigency” at the our budget are however, there has not yet been cuts become confronting us will important to fulfilling faculty, staff and there is the strong apply to our impacts. least a following cut imposed on all uh mânoa uh painless way be share their the spring 2010 semester. base budget from for a several months, best http://www.hawaii.edu/cgi-bin/uhnews?20090728160502 students, staff and faculty will be invited us is that we same time, had central future reduction levels outlined above take year futures.

this longer-term our major our and identification of resources longer at would include: on the cuts, because it community is of utmost upcoming fall programs, the savings will not be because inflicts on many a 6%. we all families and spending by an facing acceptable forward additional $14 cannot afford million – this employee unions to implement such to not be for reduction/ more security because the cuts into a shorter time to passionate agreement with uh for everyone’s number of this additional loss of revenue careers, for in arts and programs additional thoughts and ideas. this is for current near cuts because of campuswide into academic priorities and, at the reductions thankfully uh mânoa is our supporting is reductions for mânoa. for the of hawai‘I, recognize and regret imperative that we tuition increases in many activities our one-day-per month furloughs or a 5% salary significantly lessen these members of our reduction; continue all that contracts, because of their crucial relationship to no public campus additional the recognize after next year. to principles in to input, I have concluded that uh which uh least four months’ the workgroup have areas progress in student reality help problem. the student success. to including the community that involves challenges that are realized this point in simply notifying more members of world, are to achieve such must actions, cuts in our overdue repairs to provide an knowledge the “holds” on positions, and university of our to manage the need policies require account together – to discuss loa,

virginia's. that hawai’I’s revenue picture substantial with people around the reaching addition, our uh from the now.

the challenges most redirection of prioritization and near even august 12, it $11.6 million) and additional semester to which ways in is retained in impacting comprehensive labor and hawaiian still becoming established and is the in

based on faculty – we all fully future, as the equivalent of care at which we there is but to move begin those actions declaration by former president david to to generate more revenues. be federal require cooperation and understanding among substantially alleviated through other lot campus-wide forum early in this faces a $14 hawai‘inuiâkea state, because this to this support during backlog of community and our steps. therefore, we have no choice began the upcoming fall semester, the provided by chancellor

vhinshaw@hawaii.edu

--

citizens of the state commitment to our the because, as our newest school,

for campus members; and before it heavily programs will be stepping notification that, in contrast future and are (totaling because of critically they members of 2009

aloha! as we prepare of “mind in budget our of the large schools/colleges not a one-time mânoa cuts:

• maintain requirements, so it is maximize our limited when we blessed in having a university the facilities and maintenance rapid programs way they can. since sciences programs will more severe if we continue to these require result, the further reductions all year success, but that lost additional mcclain and in recent weeks, because of first date by been dealing with financial will plan for at of a of the current fiscal should be guided by the committee on the settlement in the frame.

over the past students. as we are the definitely plan improves. as cuts, the campus university. grateful eliminate native community; opportunity is an unfortunate consequence fullest extent possible, effectively, a limited that remedy our long - our campus everyone.

• plan for permanent, focus on these tough times.

mahalo nui achieve savings through retrenchment. budget we we would be those discussions and is on top accomplishing these budget at losses. reductions of more than $20 million through elimination and recommendations on likelihood forward to friends/alumni certainly also mânoa community. we the safety of our campus for creativity and do it well. following up deeply about our meeting separately – hawai’I at mânoa along action – damaging impact hinshaw

uh mânoa mânoa can maintain alleviation power” to importance to programs this month, we have reductions in staff and the hawai’I - for time, ways doing and hawaiian

• exempt must unfortunately implement steps current levels

and then have to financial future will worsen tuition increases. such however, we simply can’t wait any spend chancellor’s advisory the know, only and million could be increasing programs to challenges. in addition, many people in we planned to invest reduced services, school of an earlier 4% if there is help – I am advance notice of non-renewal of reduce our learning/research environment campus will instructional in other campus additional of that means september 1st is the expire stimulus funds which are one-time a time certainly aware, easy or compress crisis that will be felt by all of able to limited to 2.5%, while the level of our now

There are some truthful post-op nuggets here: "this additional loss of revenue careers," the Steinian "I have concluded that uh which uh least four months"; "manage the need policies"; "we all fully future"; "aloha! as we prepare of 'mind in budget'"; "grateful eliminate native community"; "opportunity is an unfortunate consequence"; "plan for permanent, focus on these tough times"; "mahalo nui achieve savings through retrenchment"; "I am advance notice of non-renewal of reduce our learning/research environment campus"; "the level of our now" and the most apt of them all: "damaging impact hinshaw."

Thus far these memos have only gestured at future consequences of the budget crisis in this state. We await the real news. But the withholding or delay of real news (by way of syntax as well as lack of information) certainly does not work in our favor.

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 11:57 AM 1 comments

Labels: budget cuts, Chancellor Hinshaw, cut-up generator, UHM football team

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Dyslexia, Syllabi, Teabagging

My son notices many things I do not. From a moving car he sees a deer a hundred yards away in a field of tall grass (in Washington State); he sees the small hands carved into the artificial rocks on a path at the UHM Art Department; he sees the small blue bird peering out of its hidden perch at the San Francisco Academy of Sciences museum. To take a walk with him is to discover what is there in front of me already. What he does not see well are letters, words, pages of writing. For him, reading involves a lot of guesswork. When he was younger and his books all included large pictures, he would carefully study the pictures and then invent the text, using the first letters of each word as his clues. The results were sometimes astonishingly close to the written story, other times as far away as that deer in the field. When his more literate friend comes over and wants to play Star Wars Mad Libs, Sangha declares that he won't follow the rules. I know he won't because he can't. But I appreciate the imagination it takes to re-invent games so that you can play them. The game of reading is hard to game, however, especially when school is rigged on the side of the good readers.

This summer we sent Sangha to Assets, a school in Honolulu that specializes in teaching dyslexic children. While Sangha mostly told us about his enrichment classes in rocket building, art, and construction, he was especially excited one day that they had talked about "dge" as part of a word. Edge, ledge, knowledge: many a dge lurks in our words. (This reminds me that during Sangha's Russian sounds phase of his aquisition of language, he once assigned the sounds "dge dge deva" to a meal of salmon and rice.") That was about the time he also sounded like a Brooklyn cop muttering under his breath, lots of "disses" and "dats" from the back seat of the family car.

My colleague, Laura Lyons, recommended Maryann Wolf's Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain . One of the book's revelations (and there are many) is that the act of reading is not natural for human beings. There is no reading center in the brain; instead, reading is an activity made up of other brain functions. Reading is adaptation. For good readers, reading is "bidirectional: we bring our life experiences to the text, and the text changes our experience of life . . . wherever we are led, we are not the same" (160). We adapt to (because of) our reading. Wolf has a marvelous few paragraphs about the ways in which our reading changes over the course of our lives, how particular books mean different things to us at different times. How true. I will often counsel students resistant to a particular text to try it again in ten years, twenty years. The analogue is the way we read our own lives differently over time, or how we read time. If, as Ashbery writes, things acquire a "sheen" in your late thirties, then my sense is our later years reduce the sheen and expand the pathos. Some of us, in any case, move from abstraction to tangibility. But in that tangibility is contained the potential for more feeling. I once detested Williams's wheelbarrow. But it's been growing on me for years now.

My son's gift is that, at 10, his world is tactile, tangible. Reading, however, is an abstraction, difficult as math was to me at his age. His reading of the world is immediate; not so his reading of his books. He's got the wheelbarrow down already, just not Williams's (or anyone's written) rendering of it.

*************

August is the month to spread the syllabic seeds, plan courses, set forth expectations, say no to cell phones, ipods, and texting in class. The syllabus is map to an undiscovered place--not a new continent, but the place you live in already whose details are still hidden. It points, like my son pointing at a bird. But that's why it's a scary thing. For me, the syllabus sets forth the promise of what books and poems can do for a (usually timid) reader; for the student, the syllabus is a mix of possibility and danger (how many tardies do an absence make?) I'll be teaching two courses this Fall, English 273: Creative Writing & Literature, and English 410: Form & Theory of Poetry. The first is an introductory course of recent vintage; I like this course because it institutionalizes the way I like to teach anyway, mixing reading and writing in equal measure. This Spring I taught it with an emphasis on documentary writing, including C.D. Wright's, One Big Self, about Louisiana prisons and Lisa Linn Kanae's Sista Tongue. This semester we'll read Eleni Sikelianos's The Book of Jon. We will also be studying and riffing off books by Craig Santos Perez, Kamau Brathwaite, Joe Brainard. And we'll begin by reading and writing haiku, poems wedded to the tangible world. The other course is upper level; in it, students think about writing as they do it. So I've put Lofty Dogmas on the reading list for its essays by poets on poetry. And, for the first time in over a decade, I'll be teaching Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris's Volume 1 of Poems for the Millennium. It's still my favorite of their anthologies. I've posted drafts of my syllabi here and will be refining them over the next few days.

***************

I found this video of an "an angry teabagger" at John Aravosis's Americablog.

I remember being in a poetry class with Alfred Corn my senior year of college. Alfred, already very much a New York City poet, hailed originally from Valdosta, Georgia. I drove through Valdosta once; my only vivid memory of the place is finding myself in a restroom with some cheerleaders. Their accents were so strong that I couldn't understand a word. One member of our college class marveled that Alfred did not himself have a southern accent. "I do when I'm angry," he responded.

Mr. Call, in the video above, has an accent. So does the woman who has taught her dog not to accept treats when they are offered by "Obama." Her anger is understated, but clear. Mr. Call's accent is from Maine; the woman's accent is southern. Both of them are angry. Both are obsessed with words. Mr. Call tells the reporter not to call his wife a "call girl." "Don't play with my words," is what he seems to be saying. And yet the jumble that follows, about his being forced to stay in the woods (literally and figuratively); about how "freedom is not free"; about people fighting for the America that's "being taken away" from him. Those words are important to him, but he does not have as much control over them as he does over the probably exhausted joke he's told all of his married life. And the dog who refuses Obama treats has been trained to recognize that some words are taste-less, not worth the reward that he takes happily when it comes from "dad" or "mom." Obama is not part of our family, in other words.

This is not to say that people with accents are haters, of course. But there's something in the intensity of their voices, their uses of words (however recycled and tired those words might be) that enables their accents to draw us in, then fling us back. There's pathos in their attentions to words and phrases--"call girl," "in the woods," "Obama"--precisely because they do not attend to their other words--"freedom," "fight," "my country"--with any awareness of what they might mean to the rest of us. I'm not sure what to make of this stew of anger, accent, and word salad, except to say I'm scared of it.

Posted by Susan M. Schultz at 11:36 AM 1 comments

Labels: Alfred Corn, dyslexia, Maryann Wolf, Proust and the Squid, syllabi, teabaggers

|

|